Everyday Things and Activism

Brandon Schechter

The Soviet Jewry movement brought a wide variety of people together, many traveling great distances and making connections across the Iron Curtain. It also involved a lot of stuff.

Objects that traversed the borders changed their meaning and value, and new things were created to support and draw attention to the Refuseniks. In the oral histories conducted by the Blavatnik Archive among activists, refuseniks, and scholars who participated in the movement, the role of material culture is a frequent subject.

The movement itself changed the meaning of objects. Alexander Smukler noted how the mere wearing of a Star of David seemed like a bold political act. He recalled how seeing two young men on the beach flaunting this Jewish symbol was a moment of awakening that drew him to them and ultimately a central role in the Refusenik movement.1 Conversely, among American activists, fear that displaying religious symbols would lead to further repression of Soviet Jewish life led organizers of Solidarity Sunday – a yearly mass rally around Purim to bring attention to the movement – to avoid their use. Malcolm Hoenlein, who organized the events recalled a religious leader cautioning him:

“Don't use sacred items, Torahs and Talliths, which we used to march in the front of the Solidarity day… Because every time the Russians see Jews inside Russia dancing with the Torah, holding a Torah, wearing a tallis, they will associated with a protest movement and they will be in danger because of it.” 2

Objects that would appear neutral or apolitical took on tremendous political weight, and religious objects were among the many things that activists brought with them on their trips to Refuseniks in the Soviet Union.

Activists in the US created a wealth of objects to remind people of the plight of Refuseniks. Readers of the New York Times and strap-hangers on the metro were confronted with ads that drew attention to Prisoners of Zion. Place mats at restaurants brought the stories of individual refuseniks to almost everyone eating pizza.3

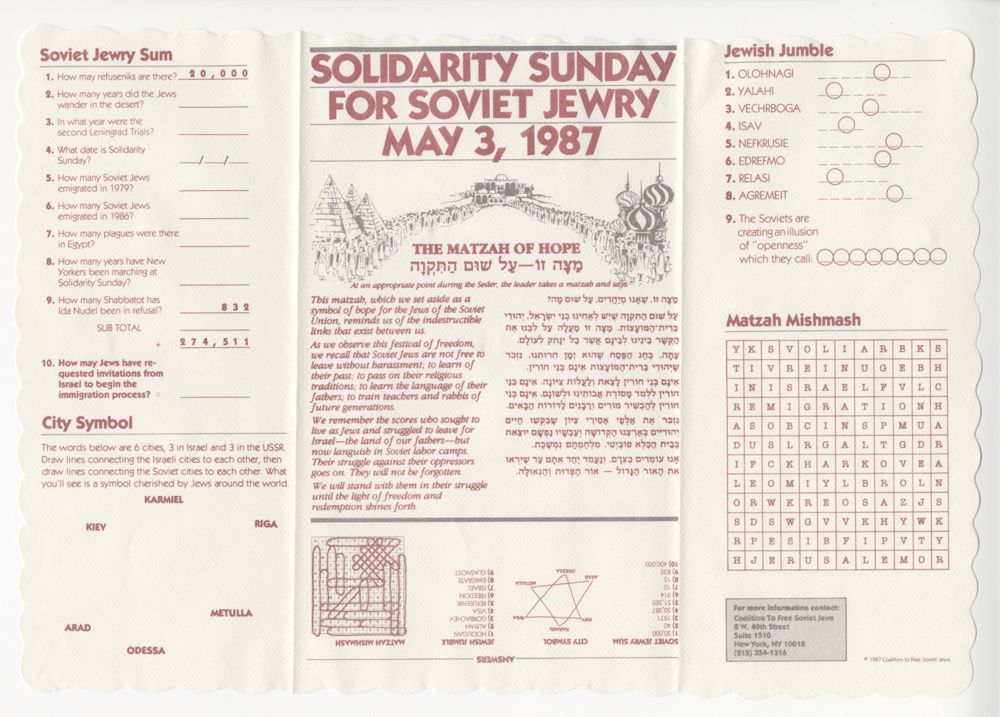

The Matzoh of Hope – a special prayer for refuseniks at Passover became a signature expression of the movement.4 The Haggadah read:

This was part of the Free Soviet Jewry movement’s call to not look away from the suffering of fellow Jews and humans.

It also wrote the current struggle into thousands of years of Jewish perseverance in a way that entered people’s everyday lives – weekly rituals and yearly holidays were infused with contemporary meaning. Mass reproduced items and advertisements meant that in the greater New York area – with its large concentration of Jews, Diplomats, students, entrepreneurs, and artists – refuseniks were constantly in the background.

More personal reminders of the refuseniks appeared in temples and on people’s very bodies. Large photographs of refuseniks appeared at tables and in temple around Holidays and seders. While Shcharanskii was in prison and Nudel forbidden to leave, posters depicting them were hung in shuls “So that when a Jew came into shul on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, he or she could not avoid realizing that while we're davening in the synagogue, they can't do that...” 5 It was suggested that an empty chair be set at the table in honor of refuseniks. Many marchers on Solidarity Sunday carried signs advocating for specific refuseniks.

Many Jews participated in “twinning” during Bar and Bat Mitzvah’s – adopting the name of a refusenik their own age who could not receive their Mitzvah due to Soviet oppression. This often included wearing jewelry with the name of their twin or another refusenik, which could be both a public and intimate reminder of the movement.6

These humble objects were an embodiment of the Soviet Jewry movement that helped hundreds of thousands of Soviet Jews reestablish themselves outside the Soviet Union and follow their conscience.

They also helped reinvigorate a sense of Jewish identity among American Jews in a period where there were greater possibilities for assimilation, and thus risks of the Jewish community declining. For many in the movement it had been precisely ignoring the suffering of Jews in Europe that had allowed the Holocaust to happen, and while Soviet oppression did not seek to physically exterminate Jews, it did seek to end the Jewish religion. Only through solidarity and advocacy could traditions be saved on both sides of the Iron Curtain, and posters, placemats, buttons, jewelry and pamphlets acted as constant reminders to this call.